Cheminformatics Intro

To see the example notebook for this intro please click here

Cheminformatics is the application of computational or computer based approaches, often referred to as in silico methods, to chemistry and chemical structures. One of the key challenges in the cheminformatics space is the featurization, or description of a molecule such that a computer can understand it. In nature, molecules are a complex combination of electronic interactions that play out on a quantum scale in 3-dimensional space. However, despite dramatic increases in computational power the field has yet to achieve this level of modeling at scale.1 Therefore, we must rely on simpler representations in order to describe a molecule.

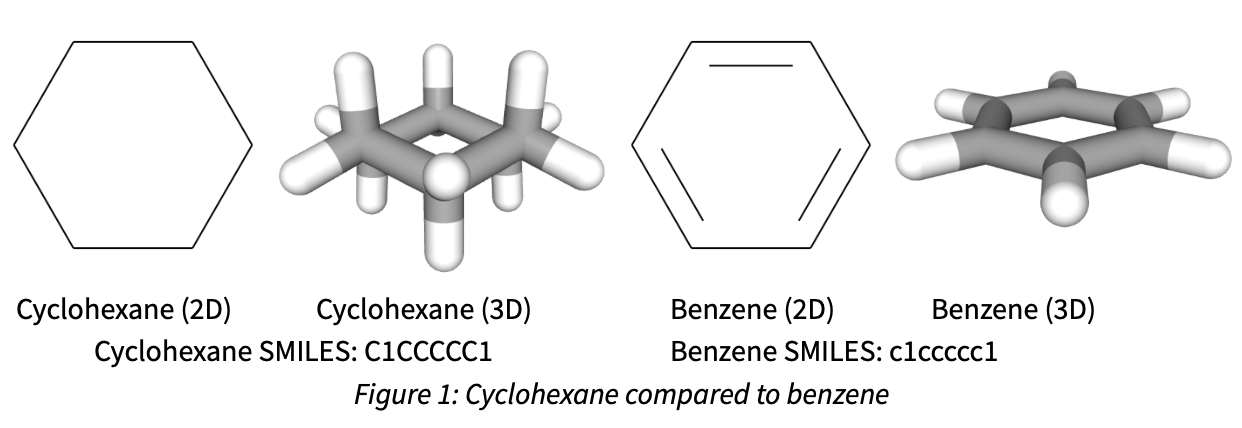

In many chemistry applications, structures are drawn to a 2D image, where atoms (assumed carbon unless otherwise specified) are connected by simple lines to form bonds. While this type of image can be effective for communication of structure, it often masks subtleties of how the molecules look in 3D space, or behave from an electronic perspective. For example, when comparing cyclohexane to benzene, the 2D structures are quite similar , with 6 carbon atoms connected by either single or double bonds, in 3D they appear to be drastically different.

(2D renderings produced with RDkit, 3D structures obtained from Pubchem

(2D renderings produced with RDkit, 3D structures obtained from Pubchem

To get started with describing molecules computationally, we can utilize SMILES strings (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System), which uses alphanumeric characters and punctuation to describe chemical structures. While there has been some work in using SMILES and natural language processing techniques from a generative modeling perspective, the SMILES strings are not typically used for chemical property modeling.2 As we can see in Figure 1, despite a very similar 6 carbon atom chemical formula, the SMILES strings are quite similar, except for the capitalization. However, SMILES representations of molecules are quite prevalent for capturing the molecular structure within datasets due to their small size and textual based representation that can be easily saved to comma separated value (CSV) or text (txt) files. The 3D structure shows the most differentiation, with cyclohexane having more 3D character than the flat benzene ring.

For property modeling, it is much more common to utilize fingerprint based approaches, where a molecule is broken down into simpler subsets of chemical structure and then vectorized, using either a one-hot or count based approaches. One common fingerprinting method is circular or Morgan Fingerprints, where a radius and vector length are pre-selected and then molecules are mapped to these values based on their molecular features. Morgan fingerprints are popular because they can be easily calculated, and can represent a vast range of structural information while still being interpreted back to structural features within the molecules.3 Unlike featurization algorithms for natural language processing such as TF-idf, the connectivity fingerprinting does not depend on the dataset of chemical structures, so there is not a risk of data leakage during the featurization process because there is no fitting step when generating the fingerprints.

The algorithm for computation of these Morgan fingerprints is the iteration over each atom within a structure and then mapping the local substructure at a given radius to the bit-vector. The morgan fingerprint algorithm as well as many other relevant cheminformatics tools are all available for us in the RDkit package.4 For two example molecules, benzene and Gleevec, if we take a radius of 2 atoms and a bit vector size of 100 (smaller than those typically utilized in models due to collisions), the Morgan representations are shown in Figure 2.

Benzene:

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

Gleevec:

[1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1,

0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0,

1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0,

1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1]

Figure 2: The radius 2, 100 bit representation of Gleevec and benzene.

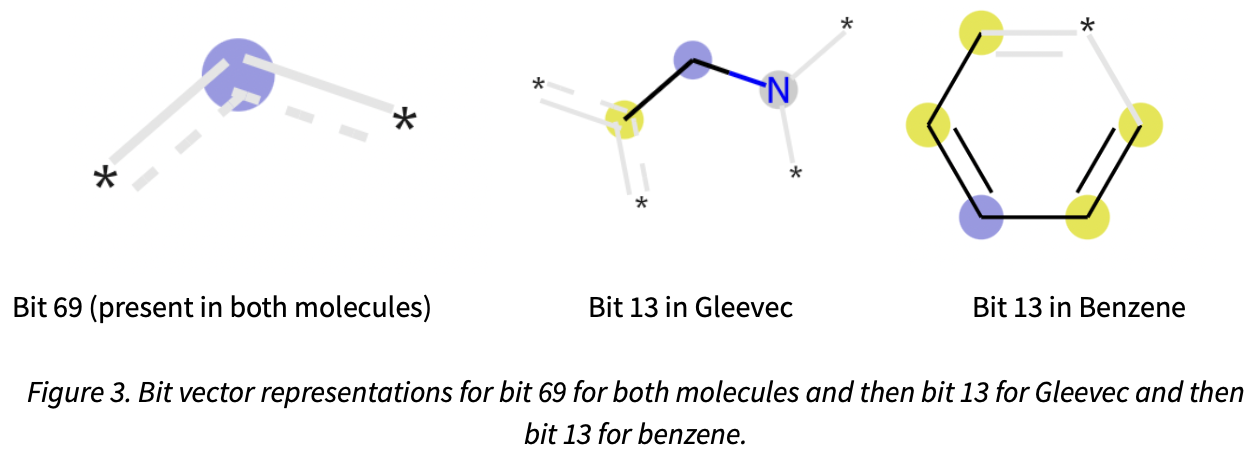

From Figure 2, we can see that the relatively simple structure of benzene is also represented by a simpler bit-vector compared with the oncology drug Gleevec. Furthermore, we can see that these molecules share values at position 13, 69 and 84. The structural representation for bit 69, is shown in Figure 3, which is a carbon sharing two aromatic double bonds, which both molecules have. However, for bit 13, we can see that this is now a collision as two different substructures are being mapped to the same position, which is why longer bit vectors of 1024 or 2048 bits are often used. Figure 3 shows the representations of these bit vectors as a 2D structure.

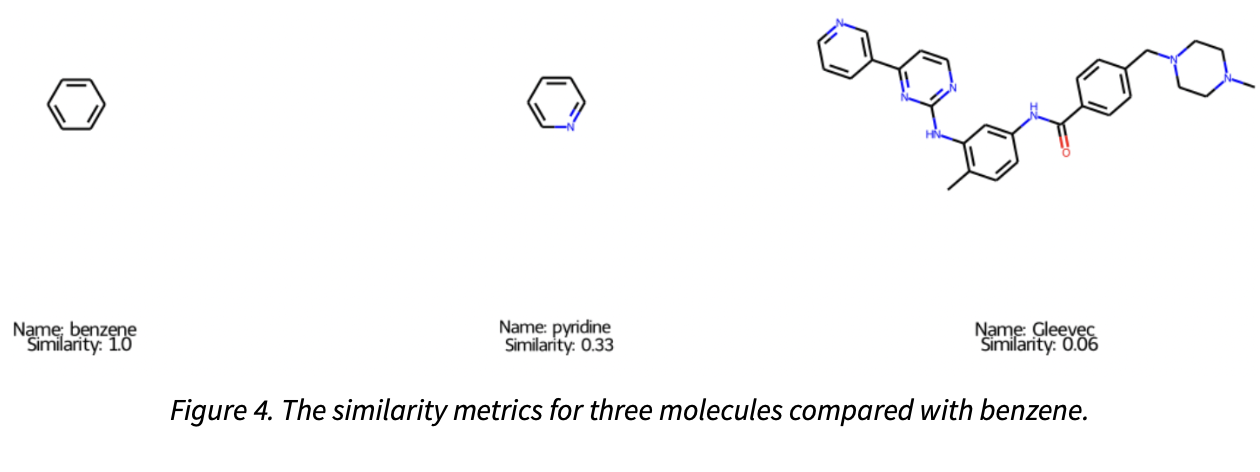

Once bit-vector representations of the molecules have been generated, many other data science tasks are then possible. For instance, we can compute the Tanimoto (Jaccard) similarity between these bit vectors as follows, where a simple nitrogen substitution on pyridine yields a similarity of 0.33, while the more elaborated oncology drug, Gleevec is only 0.06, as shown in Figure 4. For this project we decided to utilize the Morgan fingerprint as our primary means to featurize the molecules. An area for future work could be to expand this approach to utilize multiple different fingerprint types, as well as compare some of the proprietary ones which are only available within licensed software to determine if they provide improved model performance.

Sources:

- Ratcliff, L.E., Mohr, S., Huhs, G., Deutsch, T., Masella, M. and Genovese, L. (2017), Challenges in large scale quantum mechanical calculations. WIREs Comput Mol Sci, 7: e1290. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.1290

- Bian, Y., Xie, XQ. Generative chemistry: drug discovery with deep learning generative models. J Mol Model 27, 71 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00894-021-04674-8

- Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints: David Rogers and Mathew Hahn Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2010 50 (5), 742-754 DOI: 10.1021/ci100050t

- RDkit Website. https://www.rdkit.org Accessed August 2022.